The non-ASCII characters are represented using HTML entities. These include ½ for half; ¼ for quarter; ≠ for not equals; ≤ for less than or equals; ≥ for greater than or equals; ± for plus/minus; × for times; ÷ for divide. → for right arrow; ↑ for up arrow; £ for pound (currency). Superscripts and Subscripts are represented using HTML's <sub> and <sup>.

i

KDF 9 PROGRAMMING MANUAL

C O N T E N T S

Section Page

SECTION 1. THE BASIC SYSTEM 1

SECTION 2. INFORMATION REPRESENTATION 3

Number Systems 2.1 3

Rules for Number Systems 2.1.1 3

Rules of Binary Arithmetic 2.1.2 3

Conventions for Positive and Negative Binary Numbers 2.1.3 5

Conventions for expressing Binary Numbers 2.1.4 6

Numbers in the KDF 9 System 2.2 8

Integral Places 2.2.1 8

Reference to a Particular Digit 2.2.2 9

Paper Tape Code 2.2.3 10

Layout of Information inside KDF 9 2.2.4 10

SECTION 3. LOGICAL STRUCTURE 15

The Main Store 3.1 15

Input/Output Devices 3.2 15

The Nesting Store 3.3 16

Arithmetic Facilities 3.4 17

The Q-Stores 3.5 18

The Control Unit 3.6 19

The Subroutine Jump Nesting Store 3.7 19

The Director 3.8 19

SECTION 4. PROGRAMMING 21

Form of Machine Code Instructions 4.1 21

KDF 9 User Code Instructions 4.2 21

Relation to Machine Code 4.2.1 21

Mnemonic Significance 4.2.2 22

Reference Labels 4.2.3 22

The Asterisk 4.2.4 22

Manuscript and Typescript Conventions 4.2.5 23

The Comment Facility 4.2.6 23

Finish 4.2.7 24

Use of the Main Store 4.3 24

The KDF 9 User Code Compiler 4.4 25

Operation 4.4.1 25

Declarations 4.4.2 26

ii

C O N T E N T S

(Continued)

Section Page

SECTION 5. CONSTANT DECLARATIONS 27

Definition of Constants 5.1 27

Compiler Actions 5.2 27

Numeric Constants 5.3 28

Binary Constants 5.4 29

Character Constants 5.5 30

Address Constants 5.6 31

Q-Store Constants 5.7 32

Half-length Constant 5.8 32

The Instruction "SET". 5.9 33

SECTION 6. OPERATIONS ON Q-STORES 35

General Manipulative Instructions for one Q-Store 6.1 35

Special Instructions involving one part of a Q-Store 6.2 36

Operations Involving Two Q-Stores 6.3 37

Effect of Using Q0 6.4 38

Example: Setting Q-Stores 6.5 38

SECTION 7. INPUT/OUTPUT INSTRUCTIONS 41

Basic Requirements 7.1 41

Device Numbers 7.2 42

Out 4 7.2.1 43

Out 5 7.2.2 44

Out 6 7.2.3 45

Out 7 7.2.4 45

Protective Interlocks 7.3 46

Busy Device 7.3.1 46

Main Store Lockouts 7.3.2 46

Invalid Instructions or Addresses 7.3.3 47

Parity Checks 7.3.4 47

Manual Intervention 7.3.5 47

The Test Register 7.3.6 48

Magnetic Tape Units 7.4 48

Principles of Magnetic Tape Recording 7.4.1 48

Layout of Information on Magnetic Tape 7.4.2 49

Control of Magnetic Tape 7.4.3 51

Writing Fixed-Length Blocks 7.4.4 53

Reading Fixed-Length Blocks 7.4.5 54

Writing Variable-Length Blocks 7.4.6 56

Reading Variable-Length Blocks 7.4.7 57

Reverse Reading from Magnetic Tape 7.4.8 57

Positioning of Magnetic Tape 7.4.9 58

Tape Labels 7.4.10 60

Overwriting Blocks on Magnetic Tape 7.4.11 60

iii

C O N T E N T S

(Continued)

Section Page

SECTION 7. (cont.)

Paper Tape 7.5 62

Principles of Paper Tape Usage 7.5.1 62

Fixed-Length Blocks on Paper Tape 7.5.2 63

Variable-Length Blocks on Paper Tape 7.5.3 64

Control of Paper Tape 7.5.4 65

Checking Facilities on Paper Tape 7.5.5 65

The On-line Typewriter 7.6 65

Principles of Operation 7.6.1 65

Typewriter Control Instructions 7.6.2 66

The High Speed Printer 7.7 67

Mode of Operation 7.7.1 67

Off-line Printing 7.7.2 69

The KDF 9 Printer Code 7.7.3 70

SECTION 8. MAIN STORE OPERATIONS 71

General Principles 8.1 71

Direct Addressing 8.2 71

Unmodified Addresses 8.2.1 71

Modified Addresses 8.2.2 72

Modified Address with Incremented Q-Store 8.3 73

Jumps on Counters 8.4 74

Indirect Addressing 8.5 75

General Principles 8.5.1 75

Indirect Fetch-Store Instructions 8.5.2 76

The NEXT Facility 8.5.3 77

Half-Length Fetch-Store Instructions 8.5.4 77

SECTION 9. NESTING STORE MANIPULATIONS 79

SECTION 10. BASIC ARITHMETIC OPERATIONS 81

Radix Conversions 10.1 81

Principles of Radix Conversions 10.1.1 82

Data Requirements for Character-to-Binary Conversion 10.1.2 82

Operation of Character-to-Binary Conversion 10.1.3 83

Operation of Binary-to-Character Conversion 10.1.4 84

Logical Operations 10.2 84

Logical Operations - Single Word of Data 10.2.1 85

Logical Operations - Two Words of Data 10.2.2 85

Examples of Logical Operations 10.2.3 86

iv

C O N T E N T S

(Continued)

Section Page

SECTION 10. (cont.)

Addition and Subtraction 10.3 87

General Principles 10.3.1 87

Addition and Subtraction Instructions 10.3.2 88

Double-Length Sum of Single-Length Numbers 10.3.3 88

Comparison of Single-Length Numbers 10.3.4 89

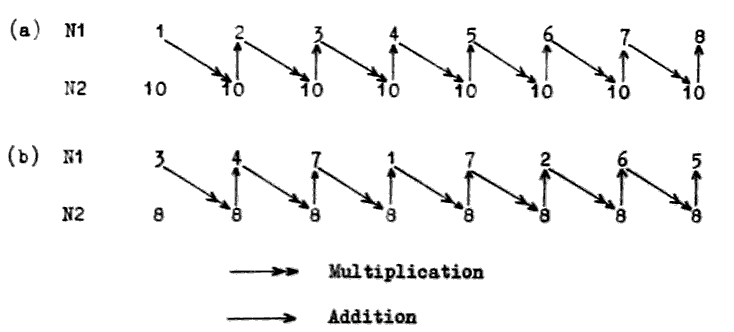

Multiplication 10.4 89

Theory of Multiplication 10.4.1 89

Multiplication on KDF 9 10.4.2 91

Division 10.5 92

Theory of Division 10.5.1 92

Division on KDF 9 10.5.2 94

Jump Instructions 10.6 95

Arithmetic Jumps 10.6.1 95

Comparison Jumps 10.6.2 96

Overflow Jumps 10.6.3 96

Unconditional Jumps without return address) 10.6.4 97

Unconditional Jumps (with return address) 10.6.5 97

Lesser Used Jump Instructions 10.7 98

SECTION 11. SUBROUTINES AND USES OF SJNS 101

Functions of a Subroutine 11.1 101

Rules for Writing Subroutines 11.2 101

Beginning of a Subroutine 11.2.1 101

Use of Stores by Subroutines 11.2.2 102

Exit from a Subroutine 11.2.3 102

Subroutines with two exits 11.2.4 103

Use of Overflow and Test Register in Subroutines 11.2.5 104

Control of Subroutine Jump Nesting Store 11.3 104

General Use of SJNS 11.3.1 104

Use of SJNS for Switches 11.3.2 105

Use of SJNS for trees 11.3.3 105

SECTION 12. FURTHER ARITHMETIC INSTRUCTIONS 107

Shift Instructions 12.1 107

General Rules for Shift Instructions 12.1.1 107

Arithmetic Shifts 12.1.2 108

Logical Shifts 12.1.3 108

Cyclic Shifts 12.1.4 109

v

C O N T E N T S

(Continued)

Section Page

SECTION 12. (cont.)

Fixed-Point Accumulative Multiplication 12.2 109

Lesser-Used Arithmetic Instructions 12.3 110

SECTION 13. FLOATING POINT ARITHMETIC 111

Principles of Floating-Point Arithmetic 13.1 111

Why Floating-Point? 13.1.1 111

Rules for Floating-Point Operations 13.1.2 111

Overflow with Floating-Point Numbers 13.1.3 112

Single-Length Floating-Point Operations 13.2 112

Floating-Point Add/Subtract 13.2.1 112

Single-Length Floating Multiply/Divide 13.2.2 113

Non-Standard Floating Numbers 13.2.3 113

Double-Length Floating-Point Operations 13.4 113

Conversions Between Fixed-And Floating-Point 13.5 115

SECTION 14. ADVANCE CONTROL 117

Operation of the Control Unit 14.1.1 117

Main Store Buffers 14.1.2 117

Programming for Advance Control 14.1.3 118

Short Loops 14.2 118

Theory of Short Loops 14.2.1 118

Procedure for Writing Short Loops 14.2.2 119

Effect of Advance Control in Short Loops 14.2.3 120

SECTION 15. THE DIRECTOR 123

Basic Functions of Director 15.1 123

Entries to Director 15.2 124

Programmed Entries to Director 15.2.1 124

Unscheduled Entries to Director 15.2.2 125

Control Entries to Director 15.2.3 125

Program Format after Compilation 15.3 126

The Program A Block 15.3.1 126

The Program B Block 15.3.2 127

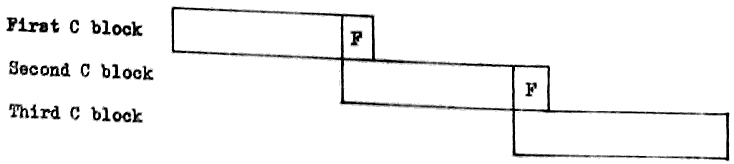

The Program C Blocks 15.3.3 128

Loading of Program Ready for Running 15.3.4 129

Typewriter Interruptions 15.4 129

vi

C O N T E N T S

(Continued)

Section Page

SECTION 16. THE USER CODE COMPILER 131

The User Code Heading Sheet 16.1 131

Mandatory Items on Heading Sheet 16.1.1 131

Optional Items on Heading Sheet 16.1.2 132

Layout of Store by Compiler 16.2 133

APPENDICES

Appendix 1 KDF 9 Paper Tape Code 135

Appendix 2 Instructions Cross-Reference List 137

(with Syllable Counts)

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure Title Facing Page

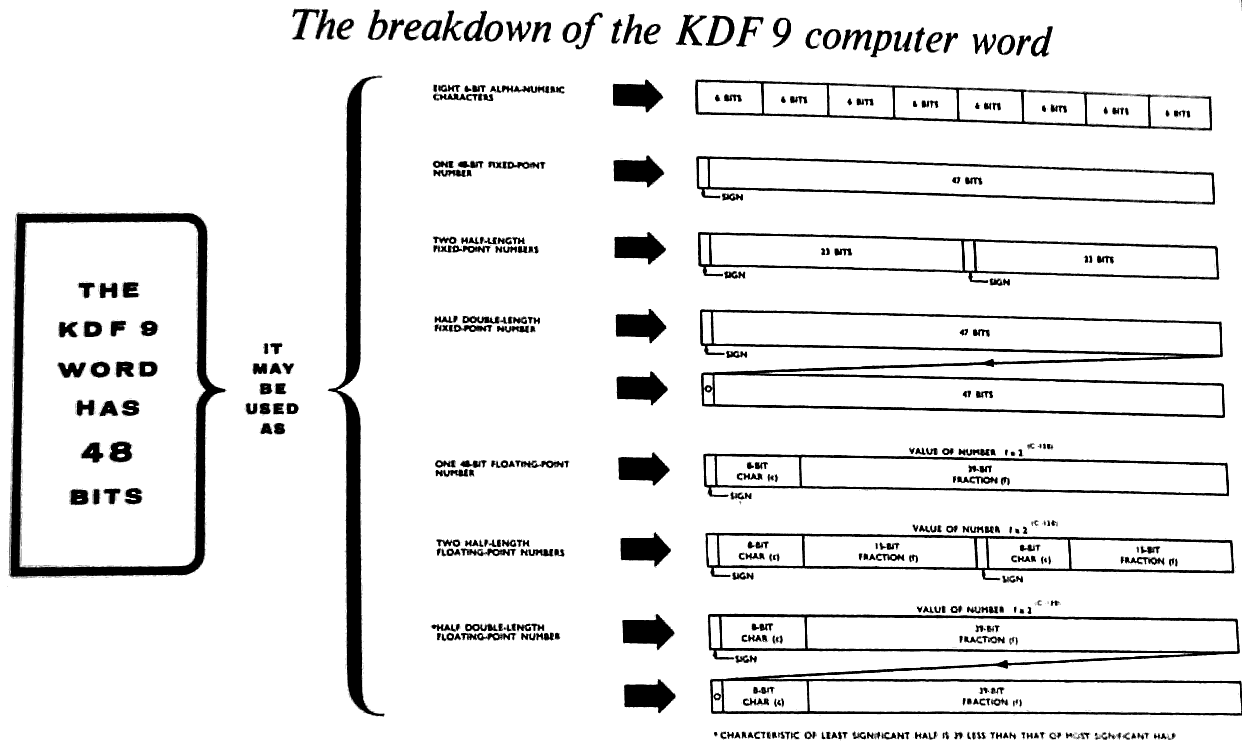

1 The breakdown of the KDF 9 computer word 11

2 The basic KDF 9 system 15

3 Analogy of a Nesting Store 16

4 Example of a KDF 9 variable-length instruction 21

5 Diagram of Magnetic Tape recording 51

6 Use of the Subroutine Jumps Nesting Store for Switches 105

INDEX

Pages vii - xiii

1

1. THE BASIC SYSTEM 1.

KDF 9 is an electronic digital computer, the high speed of operation

of which makes it an extremely valuable tool in both scientific and commer-

cial applications.

The main store is of the magnetic core matrix type providing random

access for numbers or binary patterns of 48 binary digits each, this basic

unit of information being referred to as a 'word'. Different installations

may have main stores at different sizes according to the number at modules

incorporated. A module has storage capacity for 4096 words of information,

and stores may be made up of any number of modules up to a maximum of eight

modules.

A novel feature of KDF 9 is the nesting store in which the arithmetic

operations are performed. This is a fixed address store whose mode of

operation is very economical in time; it is fully described in Para. 3.3

of this Manual.

In the design of KDF 9 great stress bas been placed on ensuring the

maximum possible efficiency of functioning in all aspects of its operation;

instructions may be obeyed while data input or output is in progress, and

the execution of instructions written consecutively in the program may in

fact proceed simultaneously inside the machine in the appropriate circum-

stances. A system of protective interlocks built into the computer ensures

that these time-saving processes proceed without damage to the program it-

self.

As an optional extra, time-sharing facilities may be fitted to the

KDF 9 system which enable up to four programs to be stored simultaneously,

control passing from one to another, whenever time is being wasted, accord-

ing to the priority grading of each program. This manual, however, will be

concerned with the standard non-time-sharing machine.

Information can be transferred to or from the computer via a wide

variety of input/output devices including paper tape units, magnetic tape

units, punched card equipment, and high speed line printers. An electric

typewriter with facilities for reading or punching paper tape or edge-

punched cards forms an integral part of the basic KDF 9 system. (See Para.

7.6). It is through this device that control is exercised over the computer,

there being no control console like those possessed by most other machines.

Because of this arrangement the typewriter copy always presents a complete

record of the operation of the computer.

The input instructions are written in a mnemonic form of the basic

machine code called User Code. This means that the maximum flexibility is

retained in the programming language, while at the same time the labour in-

volved in learning it is considerably reduced because of the easily recog-

nisable alphabetic or symbolic forms of the instructions. Translation of a

User Code program into machine code form is performed by a standard program

known as the Compiler. One or more User Code programs may be compiled in

one session on the computer, the resulting machine code program or programs

being written out on to magnetic tape. They may then be obeyed immediately

or at a later date, but in either case the Compiler program is lost from the

machine store. Therefore the Compiler program must be read into the computer

before every fresh compilation run.

2

1. The Basic KDF 9 System (cont.) 1.

Another standard program common to all KDP 9 users is known as the

Director. This is stored inside the machine at the start of each day and

can never be disturbed by any other program. Its main function is to con-

trol the operation of all other programs read into the machine by allocat-

ing the main store space and the input/output devices to be used, but it

also performs many other essential tasks which will be detailed later in

this Manual. In its complete form the Director program is used in the con-

trol of time-sharing machines, a separate and rather shorter form being

used in non-time sharing systems. A director program (of the appropriate

type) is essential for all KDF 9 machines.

3

2. INFORMATION REPRESENTATION 2.

2.1 NUMBER SYSTEMS

Information written by a programmer for the attention of a

computer takes the form of a list of data or a sequence of instruct-

ions. Notwithstanding the form in which this information is written,

e.g. alphabetic, symbolic etc., the computer can do nothing until the

information is converted into a form it is designed to understand.

KDF 9 can perform operations only on binary patterns. As a first step

towards the clarification of this statement, the binary number system

will now be bristly introduced, and its similarities with the more

familiar decimal system noted.

2.1.1 Rules for Number Systems

When counting in the everyday decimal number system, only one of

the digits 0 - 9 is needed, until it becomes necessary to specify the

number ten. Then a carry of 1 into the next column is made, so that

two digits written side by side are now required to specify the given

number. The counting process in the units column is repeated until

the next carry occurs into the tens column, and so on until the dig-

it in the tens column itself reaches ten, when a carry becomes necess-

ary into the hundreds column and three digits are now required to

specify the given number. The essential point to notice about this

familiar process is that a carry into the next most significant

digit position occurs whenever a given digit reaches the value ten.

But other number systems are conceivable which perform this carry

when a digit reaches the value nine, or eight, or indeed any value

whatever except zero and one. In particular, the very useful 'binary'

system performs this carry whenever a digit in any position reaches

the value two, so that the only digits used to represent numbers on

this scale are the digits 0 and 1. The following table lists the

decimal numbers 0 to 10 with the corresponding binary equivalents:-

Decimal Binary Decimal Binary

0 0 6 110

1 1 7 111

2 10 8 1000

3 11 9 1001

4 100 10 1010

5 101

In just the same way that a decimal number such as 123456.789

represents 1x105 + 2x104 + 3x103 + 4x102 + 5x101 + 6x100 + 7x10-1

+ 8x10-2 + 9x10-3, so a binary number such as 101101.101 represents

1x25 + 0x24 + 1x23 + 1x22 + 0x21 + 1x20 + 1x2-1 + 0x2-2 + 1x2-3 or

45.625 in decimal.

2.1.2 Rules of Binary Arithmetic

The same basic rules of arithmetic as used in decimal notation

apply equally in binary. The rules are:-

4

2. Information Representation (Cont.) 2.

(a) Addition:

1+0 = 1, 0+1 = 1, 0+0 = 0,

1+1 = 0 with 1 to carry

(b) Subtraction:

1-0 = 1, 1-1 = 1, 0-0 = 0,

0-1 = 1 and borrow 1.

(e) Multiplication:

1x1 = 1, 1x0 = 0, 0x1 = 0,

(d) Division:

1÷1 = 1, 0÷1 = 0, (division by 0 is

impossible in any scale).

Examples of the multiplication and division of numbers, which

also involve addition and subtraction, are:-

Example 1:

Decimal Binary

30 11110

x 13 x 01101

90 11110

30 00000

390 11110

11110

00000

110000110

Example 2:

2 + 1 remainder 10 + 1 remainder

3 | 7 11 |111

6 11

1 001

00

01

Just as the precision of a mechanical desk calculator is

limited by the number of decimal digit spaces available in each

register, so the precision of an electronic computer is limited

by the number of binary digit spaces available in its registers.

There are a large number of registers inside KDF 9, the vast

5

2. Information Representation (Cont.) 2.

majority of which form the main store which is used for storage

purposes only. The remaining registers in KDF 9 are those used

for the actual performance of arithmetic or manipulative operat-

ions. In contrast with the desk calculator, none of these reg-

isters is open to visual observation. The size of each register,

or the 'word length', in KDF 9 is 48 binary digits, (referred to

as 'bits').

2.1.3 Conventions for Positive and Negative Binary Numbers

It has been seen bow any positive number may be written in

binary form. It is now necessary to consider how a negative number

is to be represented inside a computer, and for this purpose the

following point should be carefully noted. If two numbers are

added to give a sum which exceeds the capacity of the register in

use, the machine result will be the true result diminished by

the quantity lost off the top end of the register. An example of

this is examined below.

When working with signed numbers there is no way of indicat-

ing a + or - sign inside a computer, and therefore some other

technique must be used. In order to understand how a negative

number can be represented in a computer, consider a computer whose

register can hold a pattern of no more than five bits. The pattern

in the register representing, say, ten, will be 01010. If the

pattern 10110 is now added to that already in the register, the

result may be calculated as follows:-

01010

+ 10110

1 00000

Note the digit in the sixth position. As the register can hold

only five digits, this sixth digit will be lost off the top end,

so that the contents of the register will now be 00000 or zero.

Therefore, so far as the machine is concerned, 10110 is the binary

representation of minus ten, since, when it is added to the binary

representation of plus ten in a five-bit register tae result is zero.

Note that in the binary form of plus ten the most significant

digit is 0, while in the binary form or minus ten the most signifi-

cant digit is 1. This digit is known as the sign digit and is

always 1 for negative numbers and 0 for positive numbers.

In general, when working with signed binary numbers, whatever is

in the most significant digit position is always the sign digit,

regardless of the size of the register. The significance of this

sign digit differs somewhat from the significance of the other dig-

its in a register. Considering again the five-bit register used

in the above example, the sign carries the value minus 24.

6

2. Information Representation (Cont.) 2.

For instance:-

01010 = -0x24 + 1x23 + 0x22 + 1x21 + 0x20 = 8+2 = 10

10110 = -1x24 + 0x23 + 1x22 + 1x21 + 0x20 = -16+4+2 = -10

Similarly, in the 48-bit register of KDF 9. the sign digit carries

the value minus 247.

A simple rule for changing the sign of 6 binary number is de-

rived from the requirement that the positive and negative binary

forms of a given number must add up to zero in the machine register.

Considering yet again the binary representation of ten in a five-

bit register, 01010, if this is added to the pattern generated by

changing all the 0's to 1's and all the 1's to 0's, the result will

be:-

01010

+ 10101

11111

If 1 is now added to this result, the outcome is:-

11111

+ 1

100000

In this result the 1 is again lost off the top end of the five-

bit register, leaving 00000 or zero. The procedure for changing

the sign of a binary number is, therefore:-

(a) Generate a second pattern by changing all the 0's to

1's and all the 1's to 0's.

(b) Add 1 to this new pattern.

The result will always be the negative of the original pattern

whatever the size of the machine register.

2.1.4 Conventions for Expressing Binary Numbers

It should be made a rule that whenever the contents of a

register are being stated, the value of every bit in the register

should be written down. If the bits at the most significant end

are zeros, they should be written down as such. For instance, 1,2,

etc., in a five-bit register should be written 00001, 00010, etc.

A complete pattern such as this, giving a picture of the entire

contents of a register, is called. 'word'.

If it were required to refer to or quote a KDF 9 word it would

be extremely cumbersome to do it as a string of forty-eight assort-

ed 0's and 1's. To avoid this tedious process, the binary pattern

7

2. Information Representation (Cont.) 2.

is partitioned into groups of three bits each and the decimal

equivalent of each group is quoted, in the order implied by the

original binary pattern. Thus the last quoted decimal digit always

corresponds to the three least significant bits. The partitioning

into groups of three must start at the right-hand or less signifi-

cant end in case the 0's at the left-hand end have not all been

filled in, so that any incomplete group appears at the left-hand

or more significant end. The following examples will illustrate

the use of this technique for a 12-bit register:-

(a) 101 110 001 100

(decimal 2956)

5 6 1 4

(b) 000 000 111 011

(decimal 59)

0 0 7 3

(c) 10 101 001

= 010 101 001 (decimal 169)

2 5 1

The quantity in example (c) should properly be written 0251.

However, when numbers are specified in this way there is a wide-

spread tendency to omit the leading 0's, so that (b) and (c)

would be written as 73 and 251, it being understood that the re-

maining digits are 0's at the more significant end.

Does this group-of-three abbreviation of a binary number

have any significance apart from its convenience as a shorthand

form of setting out the contents of a register? Evidently, from

the above examples, it does not produce the decimal equivalent

of the original binary number.

The largest value that a digit can take in this representation

is that corresponding to binary 111, or 7. What happens if 1 is

now added? The binary working for this operation is:-

111

+ 1

1000

The group-of-three representation of this result, 1000 or 001 000,

is 10. Therefore, the numbers obtained in this was belong to a

scale in which a 1 added to a 7 causes a carry of one into the next

most significant digit position, while the first digit position is

reset to 0. In conformity with the discussion at the beginning of

this paragraph, this defines a perfectly valid number system whose

base or radix is eight. Just as that number system whose base is

ten carries the name 'decimal', and that system whose base is two

carries the name 'binary', so this system whose base is eight has

been given a name. It is called the 'octal' number system.

8

2. Information Representation (Cont.) 2.

This octal system is so convenient that it is used

explicitly in the KDF 9 User Code, and it has already been shown

how useful it is when referring to binary numbers stored in the

machine.

If it becomes necessary in certain contexts to make certain

that octal and decimal numbers are not confused, the suffices 8

and 10 may be used as labels to indicate which number system is

being used. Thus (32)8 is a number in the octal scale, and

(26)10 is the same number in the decimal scale.

2.2 NUMBERS IN THE KDF 9 SYSTEM

Paragraph 2.1 introduced the number systems used in computing

techniques, and showed in a general way how a number is stored in-

side the computer as a pattern of binary digits. It is now necess-

ary to discuss in greater detail how numbers are stored inside

KDF 9 and how they are introduced into the machine from external

media.

Anyone who has used a slide rule will know that there is no

representation of a decimal point on the instrument. Powers of ten

must be borne in mind by the user and the final result adjusted

accordingly. Similarly, electronic computers do not recognise a

binary point, it being the responsibility of the programmer to keep

track of its position.

2.2.1 Integral Places

The position intended for the binary point in KDF 9 is spec-

ified by stating the number of integral places required, counting

from but excluding the sign digit at the more significant end of

the 48 bit word. Thus 47 integral places would be appropriate for

an integer, while 0 integral places would correspond to a number

entirely fractional.

The decimal number 12.375 expressed in binary is 1100.011,

but inside a KDF 9 register it might appear as:-

000 ................ 001 100 011 to 44 integral places

or 011 000 110 000 .............. 000 to 4 integral places

or in any intermediate form. Note that if a number of integral

places is specified which is outside the range 4 - 44 then sig-

nificant digits will be lost off the top end or the bottom end of

the register.

Whenever arithmetic operations ore performed inside KDF 9,

the number of integral places intended for each operand must be

remembered. The following notes may prove helpful:-

(1) Two numbers to be added or subtracted must have the same

number of integral places. Just as in decimal additions or

9

2. Information Representation (Cont.) 2.

subtraction, the binary points must be lined up one under

the other before the operation is performed, otherwise

digits will be added to or subtracted from the wrong col-

umns and an incorrect answer obtained.

(2) When two numbers are multiplied together, the number of

integral places required for the result is the sum of the

number of integral places in each of the multiplicands.

The number of integral places given by this rule is act-

ually a maximum, since they need not all contain significant

information. But because they may be needed this maximum

should always be specified. The same is true for decimal

numbers. For instance, the decimal numbers 2, 3, and 9, al

have one integral place, but the product 3x9 = 27 requires

two integral places for its specification whereas the pro-

duct 2x3 = 6 requires only one. For consistency this second

product should be written 2x3 = 06, thus preserving the two

integral places. This point can be important, as will be

seen in the next note.

(3) When one number is divided by another, the number of integral

places required for the result is the number of integral

places in the numerator less the number of integral places in

the denominator. However, in some cases extreme care has to

be exercised to ensure that an incorrect result is not ob-

tained through an erroneous application of this rule. For

instance, it appears at first sight that the result of the

decimal division 144 ÷ 12 should have one integral place.

But since the answer is 12, which has two integral places,

it will be realised that something has gone wrong. The error

will appear if it is remembered that the product 12 x 12

should give a result with 4 integral places. The fact that

the result is 144 tends to obscure this fact, because it is

not usual to think of this number as it should appear in this

context. The result of this multiplication should in fact be

written 12 x 12 = 0144, thus rendering explicit the fact that

the result has 4 integral places. In consequence the correct

form in which the division should be written is 0144 ÷ 12 = 12.

For a division such as 3240 ÷ 54 = 60 this problem does not

arise. Although the instances just quoted used illustrations

involving decimal numbers, precisely the same points apply for

binary numbers.

2.2.2 Reference to a Particular Digit in a KDF 9 Word

The 48 binary digit positions in a KDF 9 word are numbered

for reference purposes D0 - D47, with D0 the most significant or

sign digit. The abbreviation Dn is often used and is interpreted

to mean either the nth digit of a word, or a word containing a 1

in the nth position and 0's elsewhere. All binary numbers are

written with the moat significant bit D0 on the left.

10

2. Information Representation (Cont.) 2.

2.2.3 KDF 9 Paper Tape Code (See Appendix 1).

It is now appropriate to discuss the KDF 9 character code.

Most readers will know that the Morse code and the teleprinter

code represent numerals and letters of the alphabet by dots and

dashes from a buzzer or holes and the absence of holes in paper

tape. The KDF 9 code is very similar. The digits of the code

are binary digits which may be 1's or 0's in manuscript, holes

or the absence of holes in paper tape, magnetic marks or the

absence of such marks on magnetic tape, or magnetic flux in one

or the other of two directions in magnetic cores inside a com-

puter. A character is formed from six bits, some 0's and some

1's, arranged in some pattern across the tape. On paper tape

the 1's are represented by holes, and the 0's by the absence

of holes. The number of different patterns or characters that

may be constructed in this way from six bits is 64. Since pro-

vision is made in the KDF 9 character code for a generous select-

ion of punctuation marks and other symbols, and further since

both capital and small letters are to be included, there are more

than 64 items to be represented. This means that many characters

in the code must be used twice over, so that there is not a unique

one-to-one correspondence between characters on tape and symbols

to be represented. To distinguish between the two meanings of

such a character on tape, 'Case Shift' and 'Case Normal' characters

are employed. All characters on tape following a Case Normal

character are interpreted in one way, and all those following a

Case Shift character are interpreted in the other way.

The code is constructed as follows. The symbols to be

represented are listed in consecutive rows, some of these rows con-

taining two symbols and some containing only one, so that the

total number of rows is 64. These rows are then numbered from

0 to 63 in the order in which they have been listed. The character

as it appears on tape is the binary equivalent of the decimal num-

ber assigned to the symbol in question, whether or not it occurs

as one of a pair. Reference here to the tabulation showing the

KDF9 paper tape code will illustrate this discussion. Note that

those characters with only one meaning have that meaning in either

Case Normal or Case Shift.

The paper tape code, as presented in the table, concerns only

the six information bits in each character. On the tape itself

a parity bit is also included with every character, and in the case

of the 'space' and 'erase' characters an extra hole is punched

in the eighth channel. Further description of this aspect of

information representation on paper tape and also on magnetic

tape is contained in Section 7.

2.2.4 Layout of Information inside KDF 9

Following the explanation of binary numbers and the KDF 9

character code, it is now possible to indicate the methods of

storing and processing information inside the machine. The main

store of the system consists of a large number of registers which

are used as storage locations. Each location is individually

addressable and has a unique number associated with it known as

its address.

11

2. Information Representation (Cont.) 2.

(a) Information in Character Form

Since each character as read from some input medium contains

six information bits, and since the KDF 9 word-length is

48 bits, up to eight such characters may be rend into any

one register. For instance, if the set of decimal characters

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

is read into a given location, the contents of the register

will be:-

010 001 010 010 010 011 010 100 010 101

010 110 010 111 011 000

This pattern will normally be thought of in the shorthand

octal form:

21 22 23 24 25 26 27 30

If it is intended that this set of characters should repre-

sent a number, then a conversion routine must now be perform-

ed which converts the number from this character form to the

true binary form in which it will normally appear if it is

to be used in arithmetic operations. The routine for this

purpose is described in Para. 10.1.

(b) Fixed-point Numbers

For fixed-point working, the maximum value that can

be attained by any quantity (input data, partial result, or

final result) during the computation must be known to the

programmer to to within the capacity of the 48 bit word. Due

to the infinite variety of problems solved on computers, the

numbers involved may be completely fractional, completely

integral, or may contain both fractional and integral parts.

It was to allow for this variety that the concept of 'integral

places' was introduced. If the maximum size of a number

(irrespective of sign) is lees than 2P, then this number may

be stored to p integral places giving maximum precision with

no possibility of exceeding the capacity of the 48 bit reg-

ister.

(c) Double-length Fixed-point Numbers

The KDF 9 code allows arithmetic operations to be carried

out on double-length fixed-point numbers. A double-length

number has its sign digit in D0 of the more significant word,

and its 94 significant digits in D1 - D47 of the more sig-

nificant word and D1 - D47 of the less significant word. The

D0 digit of the less significant MUST be zero in any operand

used in double-length arithmetic operations and is left as

zero in any double-length result.

12

2. Information Representation (Cont.) 2.

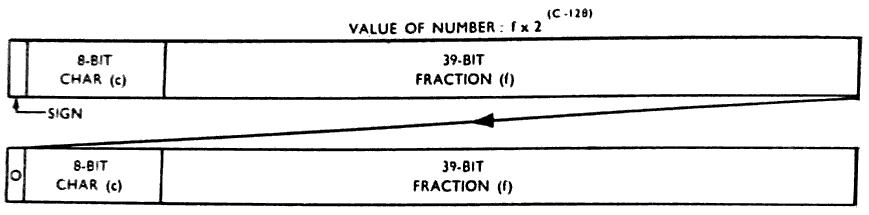

(a) Single-length Floating-point Numbers (See also Sect. 13)

The value of a floating-point number in the KDF 9

system is:-

f x 2(c-128),

where f is a signed fraction (given to zero integral places

but only 39 significant binary digits), and c in a positive

integer. The sign digit for f is D0, and the fraction bits

are D9 - D47. The positive integer c is given by D1 - D8.

Note that the floating-point representation of a number is

not unique. To achieve maximum precision the fractional

part should be in the range -½>f≥-1 or +½≤f<1,

giving 39 significant digits. A number with f between these

limits is said to be in 'standard form'. All results from

the computer will be in standard form if the original argu-

ments were in standard form. Floating divide is not guar-

anteed unless the arguments are standardised. Therefore,

only standard form floating-point numbers should be used

et all times - an instruction exists to put non-standard

numbers into standard form.

The rules for floating-point numbers may be summarised thus,

f = 0 and c = 0 for zero

0≤c≤255

-1≤f<-½ for negative numbers

0≤c≤255

½≤f<1 for positive numbers

This implies that unless f = 0, D0 and D9 are always opposite

digits - the criterion for standard form.

The maximum and minimum absolute decimal values of a number

in standard floating form are, therefore, 1.70 x 1038, and

1.46 x 10-39 respectively.

(e) Double-length Floating-point Numbers

A double-length floating-point number consists of a

single-length floating-point number in the more significant

word, with an extra 39 bits in D9 - D47 of the leas signifi-

cant word. The D0 position of the less significant word

contains a zero digit; the D1 - D8 positions contain the

binary value of (c - 39) unless c<39, in which case D0 - D47

are made all zero. The less significant word is, therefore,

an unsigned, non-standard floating-point number in its own

right.

13

2. Information Representation (Cont.) 2.

(f) Partial-length Numbers.

There is no reason why the 48 bits in a word may not be

sub-divided into two or more separate groups (possibly of

differing sizes). KDF 9 is designed to deal with a word

divided into two or three groups of equal size in certain

context: any subdivision of digits is possible, but often

leads to added complexity in isolating the individual parts,

as the penalty for the saving in storage space achieved by

packing several items into one word.

15

3. LOGICAL STRUCTURE 3.

3.1 THE MAIN STORE

The KDF 9 computer is centred about the main store, which

is arranged in modules or blocks of 4096 words, each word contain-

ing 48 binary digits. Up to eight modules may be fitted to the

machine, so that the maximum capacity of the main store is 32,768

words. The store consists of a large number of small magnetic

cores, one for each binary digit. A single module therefore con-

tains 196,608 of these cores. Each individual core may be in

either of two magnetic states, corresponding to the value (zero

or one) of a binary digit. Information is stored by setting

these cores in the appropriate magnetic states, normally in groups

of 48, i.e., one word at a time. Once information has been set in

a storage location only the sending of NEW information to that

location can replace it. Even when information is transferred from

a location a copy of the information remains intact within the store.

This transferring and automatic copying can be done as often as

required.

The words in the main store are numbered from 0 upwards. For

an installation of maximum size the words would be numbered from 0

to 32,767. The main store words are used to store (a) the necessary

control routines for the machine, (b) the instructions for the pro-

gram currently being obeyed, and (c) such data and results as are

currently being processed. Extra instructions or data may be

brought in from input devices as required, thus economising in the

use of the main store.

3.2 INPUT/OUTPUT DEVICES

Information may be transferred into the KDF 9 system and

results obtained from the system by means of a variety of input/

output devices connected directly to the main store. Up to sixteen

of these input/output devices may be fitted to the system. Each

device has its own buffer unit which exercises control over the

functioning of the device. Once a transfer from the device is in-

itiated the buffer unit can see it through to completion independent-

ly of the main computer, except for the occasional six microsecond

period during which the main store is called upon to provide or to

accept information. The input/output devices connected to the

KDF 9 system may include:-

(a) A paper tape reader reading five, seven, or eight hole

punched paper tape at a speed of 1,000 characters per

second.

(b) A paper tape punch perforating eight hole paper tape at

a speed of 110 characters per second.

(c) Magnetic tape units capable of transferring information

either to or from the computer at the rate of 40,000

characters per second.

(d) A punched card reader capable of reading 80 column cards

at 600 cards per minute.

16

3. Logical Structure of the KDF 9 System (Cont.) 3.

(e) A typewriter operating at 10 characters per second and

providing the machine operator with a record of the

operation of the machine.

(f) Devices of other kinds as required.

Any or all of the input/output devices may operate at one time.

Protective interlocks inside the machine ensure that no two input/

output operations can proceed together if they refer to a common

area of main store or to a common device. This precaution prevents

the occurrence of effects detrimental to the program. In a similar

manner computation may proceed while an input/output operation is in

progress, the system of protective interlocks again preventing any

possibility of interference between the two processes. Thus no

information any be processed inside the machine until the transfer

bringing that information into the machine from some input device

has been completed.

To assist in the control of input/output devices a one-bit

register, called the 'test register', is used to enable the program

to interrogate the various devices as to their current state. The

necessary information is transferred to the test register from the

buffer unit of the device concerned.

3.3 THE NESTING STORE

The nesting store of the KDF 9 system can hold up to sixteen

48-bit words. The mode of operation of the nesting store is com-

pletely different from that of the main store, since the storage

of words is organized in a way analogous to that used for bullets

in the magazine of a sten gun (See opposite).At the beginning of

new program the nesting store is empty. If a word, labelled 'A'

in the diagram, is fetched from the main store it is placed in the

top of the nesting store, pushing the 'spring bottom' down one unit

to make room. Further words fetched from the main store follow

the same pattern, each new arrival pushing the rest down one place

to make room for itself. Fig.3B shows the state of the nesting

store after eight words have been fetched, and Fig.3C after six-

teen have been fetched. Note the numbering of the cells of the

nesting store, N1 to N16 on the diagram. N1 always contains the

last word fetched. As there is only one way out of the nesting

store, as with the sten gun magazine, the words mast emerge in

exactly the reveres order to that in which they were inserted. The

word labelled 'A' will be the last out.

The rule for the nesting store is, therefore, "first in - last

out", except that there are a few instructions deliberately designed

to rearrange items in the nesting store.

Automatic tests inside the machine check that no more than

sixteen words have been fetched into the nesting store, and also

that a program does not attempt to remove more words than have pre-

viously been put in. A contravention of either of these restrict-

ions leads to the immediate failure of a program.

18

3. Logical Structure of the KDF 9 System (Cont.) 3.

When the overflow register is set the machine does not automati-

cally stop. It is left to the programmer to interrogate the over-

flow register at suitable intervals during the execution of his

program, end to take the necessary corrective action if he finds

that it has been set.

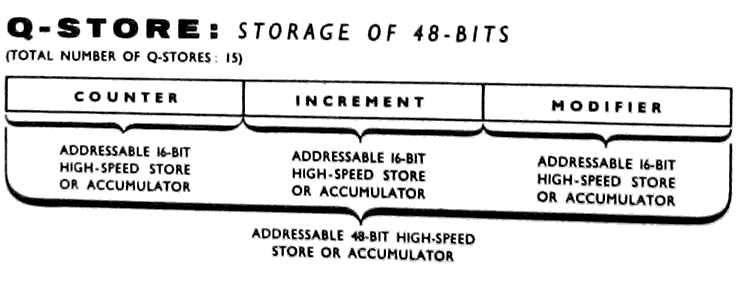

3.5 THE Q-STORES

Connected to the top of the nesting store is a set of fifteen

Q-stores numbered Q1 to Q15. The store Q0 may be used by the pro-

grammer, but for certain special reasons it always has the value

zero. A fetch from Q0 puts the value zero in N1, while any quan-

tity sent from N1 to Q0 is lost, the contents of Q0 remaining

identically zero. Each of the remaining fifteen Q-stores consists

of a 48-bit fast access register. These stores may be used for a

variety of purposes during the running of a program. These uses

include temporary storage of data or results when their presence

in the nesting store would be inconvenient, and the storage of

information which is obtained by calculation within a program but

which is required for the execution of certain instructions. For

this latter purpose the Q-store is often required to hold three

independent 16-bit binary integers. When it is divided into three

parts in this way, the sections are known respectively as:-

(a) The COUNTER (Digits D0 to D15);

(b) The INCREMENT (Digits D16 to D31);

(c) The MODIFIER (Digits D32 to D47).

Instructions are available for operating on each of the three parts

individually. No operation on one part can affect either of the

other two, i.e., no "spill" from one part to another is allowed.

19

3. Logical Structure of the KDF 9 System (Cont.) 3.

3.6 THE CONTROL UNIT

The control unit exercises control over all parts of the machine.

It extracts instructions from the main store word by word as they

are required, examines each in turn, and initiates the appropriate

actions. The instructions are obeyed sequentially as they are stored

until a transfer-of-control instruction is encountered, in which

case the sequence is broken and resumed at another point usually

specified in the control transfer instruction itself.

3.7 THE SUBROUTINE JUMP NESTING STORE

The subroutine* jump nesting store, usually abbreviated to SJNS,

is used automatically by the machine to store the return address

whenever a subroutine is entered. Since second or higher order

subroutines are quite often needed and since the return address

for the last one entered is required first, a nesting store is ideal

for this purpose because the return addresses always emerge in the

correct order. Sixteen cells are provided in the SJNS but pro-

grammers are recommended to restrict their use to fourteen cells,

leaving the remaining two for use by certain control programs nor-

mally in use on the machine. This arrangement allows a programmer

to use subroutines up to the fourteenth order and should present no

practical restrictions. Communication is provided between the top

of the SJNS and the ordinary nesting store so that the surplus re-

turn addresses may be removed or an extra one inserted as required

by the program.

The addresses stored in the SJNS are 16 binary digits in length,

of which three represent the syllable number in the range 0 - 5. The

remaining 13 hold a word address in the range 0 - 8191.

All instruction addresses in KDF 9 are of similar layout, lead-

ing to a rule that all instructions in a program moot be within the

first 8192 words of that program - the rest of the store can, of

course, be used for data. The size of the Director program does not

reduce the limit of 8192 for other programs - when the instruction

word address (13 bits) is extracted by the control unit, it adds

the necessary correction factor depending on where the first word

of the program has been placed in a full 15 bit register, thus

allowing any possible address on the final result.

3.8 THE DIRECTOR

Whenever KDF 9 is in use there will be a control program known

as the Director located at the lower numbered end of the core store.

This Director program is principally concerned with the various hold-

* Subroutines are defined in Section 11.

20

3. Logical Structure of the KDF 9 System (Cont.) 3.

ups that can occur from time to time in a program. Some of the

reasons for hold-up are:-

(a) A programming error: if one of the nesting stores is

overfilled, or if an attempt is made to remove quantities

from an empty nesting store, or an illegal instruction is

sent to control.

(b) An input/output device is required to do two things at

once, in which case the second job is held up until the

first has finished.

(c) The execution of certain standard jobs of frequent

application which have been built into the Director

program.

The program may enter the Director program by a special instruct-

ion transferring control to the Director, which then adopts a course

of action determined by the code numbers left by the program in the

top of the nesting store. At the conclusion of this process the pro-

gram is resumed at the next instruction in sequence. On a machine

fitted with time-sharing facilities the Director program also trans-

fers control from one program to the next whenever a hold-up occurs.

The choice of the next program for attention in this kind of sit-

uation is determined by Director on a priority basis.

It should be emphasized that a Director to fulfil certain

minimum requirements is always necessary in KDF 9. Certain pro-

tective interlocks designed to safeguard the running of a program

involve an automatic entrance into Director, and a Director must

be present to deal with such situations. Of course, when Director

itself is written and read into the machine there can be no such

automatic protections. Therefore Directors must be written with

much greater care than ordinary programs.

21

4. PROGRAMMING 4.

4.1 FORM OF MACHINE CODE INSTRUCTIONS

To provide immediate access to any one of the 32,768 words

in the KDF 9 main store, and also to provide address modification

facilities, some instructions require up to 24 bits to express

exactly their function. Others, such as the arithmetic instruct-

ions, (for which the data and results always appear in fixed

positions in the nesting store so that no addressing is necessary),

can be expressed precisely in only eight bits. To accommodate

these differing instruction lengths without the wastage inherent in

a fixed-length system, where every instruction occupies the space of

the longest regardless of its actual size, KDF 9 has a variable-

length instruction system; instructions may have lengths of 8, 16,

or 24 bits. The basic unit is the length of 8 bits, referred to as

one syllable, so that instructions may have lengths of one, two,or

three syllables.

As far as the operation of the machine is concerned, instruct-

ions are regarded as a succession of syllables, and in consequence

they are kept in the main store as a sequence of syllables rather

than as a sequence of words. A given instruction in the main store

may therefore overflow from one word to the next, but this does not

impair the operation of the program or of the control unit in any

way.

It is an unfortunate fact that a system for representing

instructions which is readily intelligible to programmers is not

in general in a form suitable for quick and easy interpretation

inside a computer. Either the programmer has to work in the mach-

ine code, which would make his task more difficult, or the machine

has to translate from a simplified language into its own code before

it can proceed. In KDF 9 this latter course is adopted; a special

User Code is employed to simplify programming, the computer trans-

lating from this into its own basic machine Code. This is done

automatically by a specially-written 'Compiler' program.

4.2 KDF 9 USER CODE INSTRUCTIONS

4.2.1 Relation to Machine Code

Throughout the KDF 9 User Code there is maintained an

exact one-to-one correspondence between User Code instructions

and Machine Code instructions. For each instruction that may be

written in User Code there is a single Machine Code instruction

to perform the required operation. Thus User Code has all the

flexibility of the basic Machine Code, but does not impose upon

the programmer the tedium of having to write instructions in

binary patterns.

22

4. KDF 9 Programming (Cont.) 4.

4.2.2 Mnemonic Significance

Throughout the KDF 9 User Code the individual instructions

have been kept as short as possible, while at the some time they

have been given some mnemonic connection with the operation required.

Where a conventional mathematical symbol is available, it has been

used to express the corresponding instruction in one symbol

is recognisable to all. This is possible for such instructions as

'multiply', 'divide', etc. For the other instructions the name of

the operation, or an abbreviation of the name, has been used. Wher-

ever possible the letters I and O have been excluded from these

mnemonic forms, because of possible confusion with the figures 1

and 0. Spaces occurring between symbols are ignored by the User

Code Compiler (except those in a Character Constant - see Para. 5.5).

4.2.3 Reference Labels

In KDF 9, as for any computer obeying its stored instructions

in strict sequence, it is necessary to introduce control transfer

instructions, particularly for the purpose of writing cycles or

loops. Such an instruction is often called a 'jump' instruction.

It is necessary to indicate to the machine the point to which the

jump is to be made. The technique of counting so many syllables

backward or forward has not been considered because of its extreme

fallibility and because the count would have to be corrected when-

ever the program is adjusted. Instead, provision is made for any

instruction to carry one, or, if so desired, more than one refer-

ence label. All control transfers indicate their point of resump-

tion by naming the appropriate reference label. These reference

labels are always numeric and may take values from 1 to 8,191 in-

clusive. The number of reference labels allowed is limited by the

size of the machine used for the compilation - for a machine of

8,192 words the limit will be 1,000, thus only labels in the range

1 to 1,000 would be allowable on such a machine. The actual order

in which the labels appear in the final program is immaterial. A

given reference label may be used only once although any number of

control transfer instructions may indicate a given label as their

point of resumption. Any duplication of reference labels will be

detected by Compiler and a failure indicated. The reference label

is written in front of the instruction to which it refers, and is

separated from it by a semi-colon. The semi-colon is the separator

normally used between all items in User Code. One label may be

preceded by another, if desired, separated by a semi-colon.

4.2.4 The Asterisk

In certain circumstances it is necessary for the programmer to

ensure that a particular instruction starts at the first syllable

of a new main store word. To avoid the necessity of counting the

number of syllables used in a program, with all the attendant risk of

error especially if the program is later modified, the asterisk

facility is provided. Compiler ensures that any instruction preceded

by an asterisk will be compiled as the first instruction in a new

word, any redundant spaces in the preceding word being filled with

dummy instructions. If such an instruction also requires a label

23

4. KDF 9 Programming (Cont.) 4.

the asterisk should be written before the label, since Compiler

will then compile a more efficient program.

4.2.5 Manuscript and Typescript Conventions

When writing User Code programs it is recommended that a

column be reserved on the left-hand side of the sheet for the

labels, for easy reference when it is required to trace a con-

trol transfer instruction. This means that a label always begins

a new line. Apart from this convention, User Code instructions,

separated one from the next by a semi-colon, are written one after

the other along a line. A new line may be started at any time,

but it is recommended that this be done to separate the various

stages in the logical structure of the program whenever possible.

With this kind of layout the program may be more easily followed

after it has been written. Punch operators should be instructed

to follow exactly the layout of the program in manuscript, start-

ing a new line as and when the manuscript version does. In this

way the editing characteristics of the manuscript are preserved

as carriage-returns etc., in the paper tape version, and if the

program is later reprinted from the tape the original format is

precisely reproduced.

4.2.6 The Comment Facility

Comments may be inserted at any stage of a User Code program

provided each occurs between the semi-colon terminating the pre-

vious instruction and the next instruction. These comments must

adhere to the following simple rules:-

(a) Each comment must be enclosed in round brackets.

(b) No comment may include a semi-colon or an End Message

symbol.

(c) Any round bracket opened during the course of a comment

must have the corresponding closing bracket.

(d) Each comment must terminate with the closing bracket

followed by a semi-colon.

(e) No comment may exceed 72 characters. For this purpose

all characters appearing on the input tape (including

the brackets and the terminating semi-colon) must be

counted. As one comment can directly follow another,

larger comments (if required) can be accommodated by

sub-division.

When Compiler detects an opening round bracket immediately

following a semi-colon, it recognises that it has found a comment.

It then ceases compiling while it scans the subsequent characters

for opening and closing brackets, keeping a tally of them until

the final closing bracket is identified. Then it checks again for

24

4. KDF 9 Programming (Cont.) 4.

semi-colon, the detection of which signifies the end of the

comment. Compilation is then resumed at the next instruction.

This facility enables the course of a program to be described at

the same time as it is written, the comments appearing with the

instructions on the same tape. Note that these comments do not

appear on the compiled Machine Code program tape.

4.2.7 Finish

The code of a User Code Program is indicated by the declar-

ation FINISH;→

4.3 USE OF THE MAIN STORE

The main store is used by all programs to accommodate the

instructions and the data of the problem. To make the optimum

use of the store, it is desirable to know precisely the storage

space occupied by the instructions, so that the data storage may

be begun immediately thereafter. However, the process of keeping

track of the space occupied by the instructions is cumbersome at

best. To avoid the necessity for this, in User Code the data

storage areas are referred to symbolically. It can then be left

to Compiler to determine the space required for the instructions,

and then to interpret these symbolic data addresses so that the

data are stored with no wasted space. Compiler does this simply

by adding a correction factor determined by the number of instruct-

ions need, so converting the symbolic addresses to absolute address-

es.

Normally the first word of the data storage area is referred

to in User Code by the symbolic form Y0, the subsequent words being

Y1,Y2,Y3, etc. For some applications one set of data storage loca-

tions is not sufficient. User Code, therefore, allows the addition-

al forms YA0, YA1...., YB0...., YC0...., and so on up to YZ0.... .

The forms YO0...., YI0.... are not allowed because of the risk of

confusing the letters O and I with the numbers 0 and 1. It is also

recommended that the forms YU and YV should not be used, since these

are reserved for possible use in certain control and diagnostic

routines. There are, therefore, 22 of these alternative sets in

addition to the main Y set.

It is possible that an area of main store will be required

as working space by a large subroutine. For this purpose stores

known W-stores are provided, numbered W0, W1, W2, etc. It should

be remembered that these W-stores are common to all subroutines and

should not be used for the permanent storage of information, since

one subroutine may destroy the information left in the W-store by

a previous subroutine.

It is often necessary for a program to require certain constants

during the execution of the program. User Code provide. facilities

for these, and a set of V-stores, numbered V0, V1, V2, etc., are

available for this purpose. Chapter 5 explains their use in greater

detail.

25

4. KDF 9 Programming (Cont.) 4.

Finally, it may be necessary to refer to the words in the

store absolutely. This may be done by using the addresses E0, E1,

E2, etc. E0 will be the first word of the store area allocated

to the program.

For the purposes of this manual the form Yy will be used to

represent any one of these possible forms, where y represents any

integer. Wherever Yy is used any one of the alternatives Vv, Ee,

Ww, YAy, YBy ....... YZy is permissible. The sizes of the integ-

ers e, w, y are limited only by the total capacity of the main

store.

4.4 THE KDF 9 USER CODE COMPILER

4.4.1 Operation

The KDF 9 User Code Compiler will accept User Code programs

either from paper tape or from magnetic tape, and will then pro-

cess them character by character to generate the equivalent pro-

gram in machine code instruction. During the compilation process,

the instructions are checked in turn for agreement with the per-

missible User Code forms, translated into machine code, and stored

in consecutive locations of the main store. If the Compiler has

discovered no errors, at the conclusion of the compilation run

the translated program is transferred on to tape from the main

store.

If any errors have been found this does not occur. Instead

the errors themselves are reported, three dummy instructions be-

ing inserted into the main store for every error detected. This

enables the Compiler to continue through the program, to cheek

for further errors. Therefore at the end of one compilation run,

either the correct machine code program is produced or a complete

list of all invalid instructions is given. A second compilation

run with a corrected input tape should result in a valid machine

code program.

The output from the Compiler sill be on either punched paper

tape or magnetic tape as required, and will be in the correct form

for subsequent input by the Director program loading routines. The

Compiler will require the main program to appear at the beginning

of the input tape, preceded only by such declarations as are re-

quired. The main program is followed by any subroutines it needs,

but where the library of standard subroutine is available on mag-

netic tape, these may be called for automatically and will not need

separate presentation on the input tape.

The time taken to compile a User Code program depends on the

number of instructions involved, but a rough estimate would be

about twice the time taken to read the input tape, plus an allowance

for the output. This output time is negligible for magnetic tape,

but will be very much longer should paper tape output be required.

27

5. CONSTANT DECLARATIONS 5.

5.1 DEFINITION OF CONSTANTS

A constant in KDF 9 is defined as any quantity, such as a

binary pattern, a number, or a set of characters, which is re-

quired unchanged throughout a computation or part of a computat-

ion, and which can be assigned a binary configuration by Compiler

and read in with the instructions, rather than with the data.

No matter what form the constant takes in the program the

machine will require it as a pattern of binary digits. It is

therefore necessary to arrange for all the constants to be con-

verted into binary form before the program is obeyed. This func-

tion is performed by the Compiler program, so that the resulting

Machine Code program will automatically contain the constants in

the required binary form. No special instructions need be provided

by the programmer for this purpose.

The actual instructions which introduce these constants in a

program are of two distinct kinds. The first kind puts each con-

stant into a special set of stores called V-stores, from which it

may be recalled any number of times during the operation of the

program. The second kind, by use of the instruction SET, puts the

constant into the first cell of the nesting store ready for immed-

iate use. The uses of the V-stores will be described first.

The declaration of a constant for the V-stores takes the form

Vv = the appropriate quantity. The letter v represents the number

of the particular V-store involved.

5.2 COMPILER ACTIONS

The statements on the front sheet inform Compiler how many

constant spaces are to be reserved for the program in the main

store. As each constant declaration is encountered in the program

itself, the corresponding binary pattern is generated and stored

away in the nominated V-store. In the same way, all the instruct-

ions on the User Code tape are converted into binary form and

stored in appropriate regions of the main store. On output of the

compiled machine code tape the entire contents of the store used

by the program for instructions, or constants, as filled by Compiler,

are written on to the tape. Thus when this machine code program

tape is run at any later date, the storage area allocated to the

program is filled from the tape with all the necessary data in the

form of V-stores etc., which may then be fetched to the nesting

store when required by the program.

It is to be noted that the declarations themselves do not

appear on the machine code tape. It is recommended that the con-

stant declarations should all be written in order at the head of

the User Code program, immediately following the front sheet. This

serves to emphasize that they are dealt with on compilation and not

at run time, and also makes it easier for the programmer to keep

track of the values be assigns to the individual V-stores while the

program is in preparation. Apart from this special facility for

29

5. Constant Declarations (Cont.) 5.

binary places, so that it will be stored at the lees significant

end of the 48-bit word.

The four possible forms for the declaration of a numeric

constant will now be listed. The abbreviation Vv means the V-store

constant numbered v, and z is a decimal number as defined above.

Vv = z/s :- a single-length numeric constant given to s

integral places.

VvD = z/s :- a double-length numeric constant given to s

integral places.

Vv = Fz :- A floating-point single-length numeric constant.

In this case the symbols /s are not necessary

since the number is automatically put into stan-

dard floating form.

VvD = Fz :- a double-length floating-point numeric constant.

The symbols /s are omitted as in the single-

length case.

Examples

V1 = 49/6; gives 49 to 6 integral places.

V2 = 74.6; gives rounded integer result i.e., 75 to 47

integral places.

V3 = 1/0; gives failure indication from Compiler (overlength)

5.4 BINARY CONSTANTS

Any binary pattern may be expressed in constant form for use

in a program, but for economy of space in writing it out, the octal

system is used in its actual expression. Thus a maximum of 16

octal digits will express a 48 bit binary pattern of any configur-

ation. A binary constant is always expressed in integer form. If

fewer than 16 octal digits are required a space will automatically

be left at the more significant end of the word in which it is

stored. However, should the constant be required at the more sig-

nificant end of the register, with zeros at the less significant

end, the declared octal number may be followed by the symbols /s.

The least significant digit expressed in the specification will then

be put into position s, all register positions below this being left

as zeros. In general the integer s may be chosen to position the

binary pattern anywhere along the register.

30

5. Constant Declarations (Cont.) 5.

The declaration of a binary constant takes the form:-

Vv = Bt/s where B is the label for a binary constant,

t is the binary integer expressed in

octal form,

s is the position of the least significant

bit expressed.

As before, if the symbols /s are omitted a value s = 47 is assumed.

A failure will be reported if any non-zero bit is lost off either

end during the shifting process.

5.5 CHARACTER CONSTANTS

On occasions it is useful to be able to set up constants in

character form for use when headings or comments of various sorts

are required with the results on output. For this purpose the

character constant facility is provided. Each character constant

can hold up to eight alphanumeric characters including the space

character. The word in which the constant is stored is filled in

from the least significant end. If fewer than eight characters

are used, the characters specified will be placed at the less sig-

nificant end of the word, the more significant being filled

with 'space' characters (Octal 00). Since it may be inconvenient

to have these spaces appearing in the output, it is recommended

that a character constant should always contain the full eight

characters, padded out with dummy spaces at the least significant

end if necessary. The actual characters punched on the tape

transferred into the word one at a time as they are read, filling

the word from the bottom end. If more than eight characters are

specified, a failure will result.

It is recommended that only characters in case-normal on the

Flexowriter should be used in a character constant, and that edit-

ing characters such as carriage-return, line-feed, TAB, etc.,

should be avoided. This is to minimise the possibility of errors

of interpretation when the Flexowriter operator punches the written

instructions on to tape. If the use of editing symbols cannot be

avoided, it is recommended that the word containing the carriage-

return, line-feed etc., should be expressed throughout as a

binary constant writing down the octal equivalent of every char-

acter in the the constant, and reverting to the character con-

stant form for the subsequent constants. This means effectively

that the only characters appearing in character constants are

capital alphabetic characters, numeric digits, and the 'space'

character. A semi-colon or end-message symbol must never be

included as one of the eight characters.

The declaration of a character constant takes the form

Vv = C (string of up to eight characters);

31

5. Constant Declarations (Cont.) 5.

where C is the label for a character constant and the semi-colon

is the normal terminator for all User Code instructions, neither

being included in the count of 8 characters.

As an example, V7 might be required as a terminator for

printed results. The specification

V7 = C END˽DATA;

would result in the eight characters specified being placed in V7.

5.6 ADDRESS CONSTANTS

It is often necessary to know the actual address of the main

store word at which a particular quantity is stored. Since such

addresses are not known until the program is compiled, it is reason-

able to expect Compiler to provide this information where required.

So in User Code programs the addresses of main store words are

written symbolically, the absolute addresses being substituted by

Compiler on compilation. Each address obtained in this way defines

both the word and the syllable number of the location, so both data

and instructions may be located precisely in the main store. If

a data address is called for, the syllable number given will always

be zero since an item of data is always stored starting at the be-

ginning of a new word. An instruction on the other hand may begin

at any syllable of a word.

The form of the declaration for an address constant is

Vv = AYy where A is the label for an address constant,

Yy is the symbolic address of the word

required; y being an integer.

The address Yy may be replaced in this declaration by any of the

following valid forms of address:-

(a) YAy, YBy ..... YZy excluding YIy and YOy;

(b) Ww;

(c) Vv, VvPp, VvLl or their half-length equivalents;

(d) Rr, Pp, Ll, RrPp, RrLl.

When the address required is that of a DATA store (i.e. for

Yy or any of the forms in (a), (b), or (c) above) it may be that

the HALF LENGTH address is required. This is obtained by adding

U or L after the data word name to indicate Upper or Lower half.

Compiler will then give the true half length address required,

doubling the word number and adding one if necessary. To ill-

ustrate by example, the two declarations:

32

5. Constant Declarations (Cont.) 5.

V1 = AY14;

V2 = AY14L;

would give the addresses (assuming that Y0 happened to fall in

word 640) 654 - calculated as 640 plus 14 - and 1309 - calculated

as 640 plus 14, then doubled and one added for the lower half.

Addresses of the form in (d) above are all INSTRUCTION add-

resses and will always appear in syllable/word number form, as

required for the jump nesting store.

5.7 Q-STORE CONSTANTS

It has been mentioned in Para. 3.5 that a Q-store will often

hold three independent 16 bit signed integers, and that for this

reason it may be referenced as three integers c, i, and m. c is

the counter, stored in bits 0 - 15; i is the increment, stored

in bits 16 - 31; and m is the modifier, stored in bits 32 - 47.

The declaration of a Q-store constant takes the form

Vv = Q c/i/m where Q is the label for a Q-store constant.

c, i,and m represent signed integers limited to the range -32768

to +32767. This range is the greatest that can be accommodated

in 16 bits.

As it is often necessary to put addresses into Q-stores, any

of the valid forms of address given in Para. 5.6 above may be

used to replace the integer in one, two, or all three of the pos-

itions in a Q-store. A typical declaration of this kind is of

the form Vv = Q c/AYy1/AYy2, where y1 and y2 are integers.

5.8 HALF-LENGTH CONSTANTS

Facilities exist in KDF 9 for half-length fetching and

storing, and so provision has been made for the setting of half-

length constants. With one exception, any kind of constant may

be stored as a half-length constant. The exception is the Q-store

constant which does not lend itself to half-length manipulation.

The procedure for setting a half-length constant in some V-store

word is, first, to specify the constant itself, remembering that

it may not exceed a length of 24 bits, and then to state whether

it is to be stored in the upper (more significant) or lower

(less significant) half of the destination word.

The two forms for a half-length constant declaration are:-

VvU = (specification). This will be stored in the upper

half (D0 - D23) of the constant

store v.

33

5. Constant Declarations (Cont.) 5.

VvL = (specification). This will be stored in the lower

half (D24 - D47) of the constant

store v.

In these two declarations, (specification) may take any of the

forms given in paragraphs 3, 4, 5 or 6 above, e.g., VvU = z/s,

VvL = AYy, etc.

5.9 THE INSTRUCTION 'SET'

There exists a completely different method of introducing

integer constants into a program, by use of the instruction SET.

SET is a three-syllable instruction which is obeyed by the machine

every time it is encountered during the operation of a program.

It allows a signed integer of not more than 16 bits to be stored

actually amongst the instruction syllables. When SET is obeyed